Software Architecture: The Bad Parts

Table of Contents

- Table of Contents

- Hello, world!

- The project

- The Bad Part: Wireframe Driven Development ️

- The implementation

- Changes!

- Change One

- Change Two

- Change Three

- Other changes

- Prediction of Alert evolution

- When we know more, let's check the diagram again

- The Bad Parts

- The Bad Part: Noun(ing)

- The Bad Part: No separation of read and write models

- The Bad Part: No Clear Contexts

- The Bad Part: Context violation / Cross-Context Coupling

- The Bad Part: Dependency Injection over Events

- The Bad Part: Leaking the Domain

- The Bad Part: No Ubiquitous Language

- The Bad Part: No Actual Design Phase

- The Bad Part: Instrastructure over domain

- The Bad Part: Data Coupling

- Wrap-up

Hello, world!

Hello, Internet citizens! 👋

Do you want to learn about BAD ARCHITECTURE PRACTICES? Do you think you are free of them? Because I made all possible mistakes on my way! 😅

Do you want to go through a detailed example and see how poor or naive approach to architecture can turn your components into God Objects?

Yeah. I know you want to.

Do you want to read about context coupling? About how starting from nouns is bad? About mixing read and write models?

Tighten your seat belt and let's hit the road!

•••

I've been asked a question recently after one of my presentations that sounded, more or less, like this: "But what for? Why should I change the way I work right now and introduce a more complex solution instead"? That was a talk I called "Baby steps in Event Sourcing". I replied then that I don't think this is necessarily a more complicated approach; rather, it's a matter of our customs and experience. I also responded with a question about whether you (the participant) find your current and past projects straightforward. Were those projects weighed down by bugs popping out of nowhere?

But, the question was good, though. Really good.

It's not easy to answer that one. How to bridge the gap between knowledge and experience?

And it came to me. How was that in my case, I asked myself. I simply spotted how bad and messy the codebase can become.

The only way for me, as the presenter, is to demonstrate how bad software-engineering practices devolve the project into a big ball of mud, convert classes into God Classes, and make you a big fan of Italian cuisine as your code becomes spaghetti.

•••

The title of this article was inspired by Douglas Crockford's "JavaScript: The Good Parts", as well as Neal Ford's "Software Architecture: The Hard Parts".

•••

You'll find the full implementation of this article's example in this repo and branch.

•••

Let's treat this article as the explanation why people should think about the architecture. Back in the days that was for me a revelation and the beginning of the road towards events. Moving from CRUD to events is less about technology and more about changing how we think. Events aren’t more complex or time-consuming — clinging to bad practices is. So... let's dive into the bad practices. And make the code scary!

•••

I focused on a few fundamental Bad Parts; topics related to Event-Driven Architecture are intentionally out of scope.

The project

First, let's talk about the requirements we'll be working on. Meet the client, Janek.

Here's the text format of the image content, in case you like it more.

Context

- Janek owns a company called “JanMed” (previously “JanWątroba”)

- Janek has a network of ten laboratories in Poland 🇵🇱

- The laboratories have technicians and equipment necessary for liver examinations

- Janek wants to digitize the process of monitoring patients’ health and lay off part of the staff

Acceptance criterias

- AC1. My system receives the patient’s test results: alanine aminotransferase (ALT – U/L) and liver fibrosis level on the METAVIR scale F0–F4 from elastography.

- AC2. ALT above 35 U/L for women / 45 U/L for men generates a small alert.

- AC3. Fibrosis levels F1, F2, F3, and F4 generate a small alert.

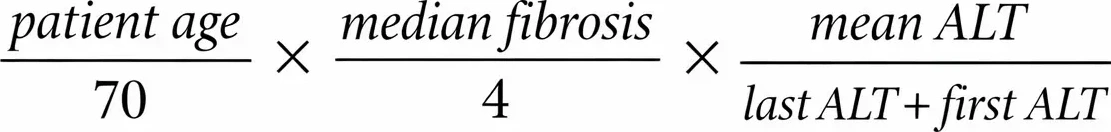

- AC4. After three consecutive alarming ALT–fibrosis result pairs, taken at intervals of at least one month, we calculate the liver cancer risk level using the formula:

- AC5. If the calculated liver cancer risk level is greater than 0.3, we generate a large alert.

- AC6. A doctor may resolve a large alert → this resolves all small alerts.

- AC7. A doctor may resolve small alerts, but when a large alert appears, small alerts cannot be resolved.

- AC8. No new alerts can be generated if a large alert has not been resolved.

The Bad Part: Wireframe Driven Development ️

The team meets for a planning session. The epics have already been prepared by (and here comes one of the possible roles) Project Leader/Team Leader/(Proxy) Product Owner. The epics have been prepared based on detailed work by a UX designer who examined the users' journey. All personas have been discovered — a patient, a medical doctor, and a laboratory technician.

The epics, along with linked designs, are:

- Authentication (registration, logging in)

- Laboratory app (measurements registration)

- Patient app (viewing measurements, alerting)

- Medical doctor app (viewing patients, alerting, resolving alerts)

- Admin Panel

During the long planning session, the backend developers concluded, based on the wireframes, that a few REST API endpoints are needed:

- Adding measurements, that is ALT blood results and liver fibrosis levels. On measurement registration, there will be a check for whether an alert should be raised.

- Resolving and getting alerts

- CRUD for patients

- Endpoints for the integration with an OIDC provider, like Keycloak or AWS Cognito

The pain: Wireframe driven-development

Does this process sound familiar? If so, that might be you, who will finally break the bad cycle.

Relying fully on UX wireframes and designs and treating them as the architecture is a real pain, because views often aggregate a lot of information where logically we expect clear separation.

Look at Image 2, where you can see a results search page on Amazon.

Do you think the implementation was so naive that Amazon stores product instances along with data regarding special offers, ad origin, rating, number of comments, prices, and delivery estimation?

The implementation

Class Diagram

Once the development team wrote down the REST API endpoints, the team discovered the main resources. These are:

MeasurementAlertUser

This domain language, these words, these nouns describe everything that happens in the system and they map perfectly to the API endpoints. Someone created an Architecture Decision Record describing the motivation behind the decision to split the API this way and not another, and as the final documentation monument, the developer attached a UML class diagram. See Image 3.

User has Measurement and Alert, which makes sense because User has these relations, right?

The most interesting is the Alert class, which has the following behaviors: ⚡

// Checks if ALT value triggers an alert based on sex-specific thresholds (>45 for male, >35 for female)

static shouldTriggerAltAlert(value: number, sex: Sex): boolean

// Checks if fibrosis value triggers an alert (value between 1 and 4 inclusive)

static shouldTriggerFibrosisAlert(value: number): boolean

// Finds pairs of ALT and fibrosis measurements from the same day that both trigger alerts

static findAlarmingPairs(measurements: Measurement[], user: User): AlarmingPair[]

// Finds valid consecutive pairs that are at least one month (30 days) apart

static findValidConsecutivePairs(alarmingPairs: AlarmingPair[], requiredCount: number = 3): AlarmingPair[]

// Calculates liver cancer risk based on age, median fibrosis, and ALT values

// using the formula: (age/70) * (medianFibrosis/4) * (meanALT/(lastALT + firstALT))

static calculateLiverCancerRisk(validPairs: AlarmingPair[], user: User): number

// Checks if the risk level requires a big alert (threshold: >0.3)

static shouldRaiseBigAlert(riskLevel: number): booleanDatabase diagram ️

Once we designed the classes, we can decide what tables we need. The matter is simple. Three tables are all we need. Check out Image 4. ✨

Alerts and Measurements refer to Users. Logical, right?

There's a chance you learned about database normalization and the normal forms. If you did, you lucky bastard! You'll be able to tell your kids about that in one sentence along with CDs, tapes, walkmans, etc.

Probably the schema is at least in 2NF, as none of the non-prime attributes (that is, one not part of any candidate key) is functionally dependent on only a proper subset of the attributes making up a candidate key. Hehe 😀😀😀

The architecture ️

Right. The architecture. Architecture is a word.

We all know the Layered Architecture. We've been taught it. It's everywhere. Similarly to other "Architectures." But this one also seems easy.

So, please look at the Image 5.

The controllers (REST API) refer to the Application layer (services), which refers to the Domain layer and the Persistence layer (repositories). OK, maybe it's a slightly twisted version of the pattern, because the Domain itself does not refer to the repositories directly but rather operates on "clean" data. Normally, the Domain layer refers to the Persistence layer. But hey, who told you that I want to implement the worst version of all possible implementations?

The code

Software engineers are not the ones to write some docs, so let's go to some hard coding, shall we?

I will present you some more interesting parts of the implementation.

The whole thing is implemented in Node.js/TypeScript. If you're not into this tech stack, I'm pretty sure the codebase will still be readable to you.

Remember, you can check the full implementation in this repo and on this branch. You can also check the commit history.

First, let's look at the domain/Alert.ts:

import {

Entity,

PrimaryGeneratedColumn,

Column,

ManyToOne,

CreateDateColumn,

UpdateDateColumn,

} from 'typeorm'

import { User, Sex } from './User.js'

import { Measurement, MeasurementType } from './Measurement.js'

export enum AlertType {

SMALL = 'small',

BIG = 'big',

}

export interface AlarmingPair {

alt: Measurement

fibrosis: Measurement

date: Date

}

@Entity('alerts')

export class Alert {

@PrimaryGeneratedColumn('uuid')

id!: string

@Column({

type: 'enum',

enum: AlertType,

})

type!: AlertType

@Column({ default: false })

resolved!: boolean

@ManyToOne(() => User, (user) => user.alerts)

user!: User

@Column()

userId!: string

@CreateDateColumn()

createdAt!: Date

@UpdateDateColumn()

updatedAt!: Date

// AC2: Check if ALT value triggers alert

static shouldTriggerAltAlert(value: number, sex: Sex): boolean {

const threshold = sex === Sex.MALE ? 45 : 35

return value > threshold

}

// AC3: Check if fibrosis value triggers alert

static shouldTriggerFibrosisAlert(value: number): boolean {

return value >= 1 && value <= 4

}

// AC4: Find alarming pairs from measurements

static findAlarmingPairs(

measurements: Measurement[],

user: User,

): AlarmingPair[] {

const alarmingPairs: AlarmingPair[] = []

// Group measurements by date (same day)

const measurementsByDate = new Map<string, Measurement[]>()

for (const m of measurements) {

const dateKey = m.measuredAt.toISOString().split('T')[0]

if (!measurementsByDate.has(dateKey)) {

measurementsByDate.set(dateKey, [])

}

measurementsByDate.get(dateKey)!.push(m)

}

// Find alarming pairs

for (const dateMeasurements of measurementsByDate.values()) {

const altMeasurement = dateMeasurements.find(

(m) => m.measurementType === MeasurementType.ALT,

)

const fibrosisMeasurement = dateMeasurements.find(

(m) => m.measurementType === MeasurementType.FIBROSIS,

)

if (altMeasurement && fibrosisMeasurement) {

const isAltAlarming = Alert.shouldTriggerAltAlert(

altMeasurement.value,

user.sex,

)

const isFibrosisAlarming = Alert.shouldTriggerFibrosisAlert(

fibrosisMeasurement.value,

)

if (isAltAlarming && isFibrosisAlarming) {

alarmingPairs.push({

alt: altMeasurement,

fibrosis: fibrosisMeasurement,

date: altMeasurement.measuredAt,

})

}

}

}

return alarmingPairs

}

// AC4: Find valid consecutive pairs (at least one month apart)

static findValidConsecutivePairs(

alarmingPairs: AlarmingPair[],

requiredCount: number = 3,

): AlarmingPair[] {

if (alarmingPairs.length < requiredCount) {

return []

}

// Sort by date descending

const sorted = [...alarmingPairs].sort(

(a, b) => b.date.getTime() - a.date.getTime(),

)

const validPairs: AlarmingPair[] = []

for (const pair of sorted) {

if (validPairs.length === 0) {

validPairs.push(pair)

} else {

const lastPair = validPairs[validPairs.length - 1]

const daysDiff = Math.abs(

(pair.date.getTime() - lastPair.date.getTime()) /

(1000 * 60 * 60 * 24),

)

if (daysDiff >= 30) {

validPairs.push(pair)

if (validPairs.length === requiredCount) {

break

}

}

}

}

return validPairs.length === requiredCount ? validPairs : []

}

// AC4: Calculate liver cancer risk

static calculateLiverCancerRisk(

validPairs: AlarmingPair[],

user: User,

): number {

const age =

(new Date().getTime() - user.dateOfBirth.getTime()) /

(1000 * 60 * 60 * 24 * 365.25)

const fibrosisValues = validPairs.map((p) => p.fibrosis.value)

const medianFibrosis = fibrosisValues.sort((a, b) => a - b)[

Math.floor(fibrosisValues.length / 2)

]

const altValues = validPairs.map((p) => p.alt.value)

const meanALT = altValues.reduce((sum, v) => sum + v, 0) / altValues.length

const lastALT = validPairs[0].alt.value

const firstALT = validPairs[validPairs.length - 1].alt.value

return (age / 70) * (medianFibrosis / 4) * (meanALT / (lastALT + firstALT))

}

// AC5: Check if risk level requires big alert

static shouldRaiseBigAlert(riskLevel: number): boolean {

return riskLevel > 0.3

}

}The Alert class is a TypeORM entity. It contains a few static methods that encapsulate the business logic to be used in a related service.

Basically, the goal is to find the three most recent measurement pairs that triggered small alerts. If those exist, then a big alert should be raised.

Now, see how services/AlertService has been implemented:

import { AlertRepository } from '../repositories/AlertRepository.js'

import { MeasurementRepository } from '../repositories/MeasurementRepository.js'

import { Alert, AlertType } from '../domain/Alert.js'

import { User } from '../domain/User.js'

import { MeasurementType } from '../domain/Measurement.js'

import { AppDataSource } from '../core/infrastructure/database.js'

export class AlertService {

private alertRepository: AlertRepository

private measurementRepository: MeasurementRepository

constructor() {

this.alertRepository = new AlertRepository()

this.measurementRepository = new MeasurementRepository()

}

async getAlertById(id: string): Promise<Alert | null> {

return await this.alertRepository.findById(id)

}

async getAlertsByUserId(userId: string): Promise<Alert[]> {

return await this.alertRepository.findByUserId(userId)

}

async getUnresolvedAlertsByUserId(userId: string): Promise<Alert[]> {

return await this.alertRepository.findUnresolvedByUserId(userId)

}

async getAllAlerts(): Promise<Alert[]> {

return await this.alertRepository.findAll()

}

// AC2-AC8: Check measurement and trigger alerts

async checkMeasurement(

user: User,

type: MeasurementType,

value: number,

): Promise<void> {

// AC8: No new alerts if unresolved big alert exists

const unresolvedBigAlert =

await this.alertRepository.findUnresolvedBigAlertByUserId(user.id)

if (unresolvedBigAlert) {

console.log('Cannot generate new alerts - unresolved big alert exists')

return

}

// AC2: Check ALT thresholds

if (type === MeasurementType.ALT) {

if (Alert.shouldTriggerAltAlert(value, user.sex)) {

await this.raiseSmallAlert(user)

}

}

// AC3: Check fibrosis levels F1-F4

if (type === MeasurementType.FIBROSIS) {

if (Alert.shouldTriggerFibrosisAlert(value)) {

await this.raiseSmallAlert(user)

}

}

// AC4: Check if big alert should be raised

await this.checkIfBigAlertShouldBeRaised(user)

}

// Create a small alert

private async raiseSmallAlert(user: User): Promise<Alert> {

const repository = AppDataSource.getRepository(Alert)

const alert = repository.create({

type: AlertType.SMALL,

user,

userId: user.id,

})

return await repository.save(alert)

}

// AC4-AC5: Check if big alert should be raised based on measurements

private async checkIfBigAlertShouldBeRaised(user: User): Promise<void> {

// Get all measurements for the user

const measurements = await this.measurementRepository.findByUserId(user.id)

// Find alarming pairs

const alarmingPairs = Alert.findAlarmingPairs(measurements, user)

// Find valid consecutive pairs (at least 3, one month apart)

const validPairs = Alert.findValidConsecutivePairs(alarmingPairs, 3)

if (validPairs.length === 0) {

return

}

// Calculate liver cancer risk

const riskLevel = Alert.calculateLiverCancerRisk(validPairs, user)

// AC5: Raise big alert if risk > 0.3

if (Alert.shouldRaiseBigAlert(riskLevel)) {

await this.raiseBigAlert(user)

}

}

// Create a big alert

private async raiseBigAlert(user: User): Promise<Alert> {

const repository = AppDataSource.getRepository(Alert)

// Check if big alert already exists

const existingBigAlert =

await this.alertRepository.findUnresolvedBigAlertByUserId(user.id)

if (existingBigAlert) {

return existingBigAlert

}

const alert = repository.create({

type: AlertType.BIG,

user,

userId: user.id,

})

return await repository.save(alert)

}

// AC6-AC7: Resolve alert

async resolveAlert(id: string): Promise<boolean> {

const alert = await this.alertRepository.findById(id)

if (!alert) {

throw new Error(`Alert with id ${id} not found`)

}

const repository = AppDataSource.getRepository(Alert)

// AC6: When resolving a big alert, resolve all small alerts

if (alert.type === AlertType.BIG) {

await repository.update(

{

userId: alert.userId,

type: AlertType.SMALL,

resolved: false,

},

{ resolved: true },

)

alert.resolved = true

await repository.save(alert)

return true

}

// AC7: Small alerts cannot be resolved if a big alert exists

if (alert.type === AlertType.SMALL) {

const unresolvedBigAlert =

await this.alertRepository.findUnresolvedBigAlertByUserId(alert.userId)

if (unresolvedBigAlert) {

console.log('Cannot resolve small alert - unresolved big alert exists')

return false

}

alert.resolved = true

await repository.save(alert)

return true

}

return false

}

async deleteAlert(id: string): Promise<void> {

await this.alertRepository.delete(id)

}

}The service orchestrates the Alert entity and the AlertRepository. The most important method is checkMeasurement, which determines whether any alert should be raised. ⚡

At the end, let's take a quick look at the MeasurementService. It handles the side effect of checking and potentially raising alerts:

import { MeasurementRepository } from '../repositories/MeasurementRepository.js'

import { UserRepository } from '../repositories/UserRepository.js'

import { Measurement, MeasurementType } from '../domain/Measurement.js'

import { AppDataSource } from '../core/infrastructure/database.js'

import { AlertService } from './AlertService.js'

export class MeasurementService {

private measurementRepository: MeasurementRepository

private userRepository: UserRepository

private alertService: AlertService

constructor() {

this.measurementRepository = new MeasurementRepository()

this.userRepository = new UserRepository()

this.alertService = new AlertService()

}

async addMeasurement(

userId: string,

type: MeasurementType,

value: number,

measuredAt: Date = new Date(),

): Promise<Measurement> {

const user = await this.userRepository.findById(userId)

if (!user) {

throw new Error(`User with id ${userId} not found`)

}

// Create and save measurement

const repository = AppDataSource.getRepository(Measurement)

const measurement = repository.create({

measurementType: type,

value,

measuredAt,

user,

userId: user.id,

})

const savedMeasurement = await repository.save(measurement)

// Trigger alert checking

await this.alertService.checkMeasurement(user, type, value)

return savedMeasurement

}

async getMeasurementById(id: string): Promise<Measurement | null> {

return await this.measurementRepository.findById(id)

}

async getMeasurementsByUserId(userId: string): Promise<Measurement[]> {

return await this.measurementRepository.findByUserId(userId)

}

async getAllMeasurements(): Promise<Measurement[]> {

return await this.measurementRepository.findAll()

}

async deleteMeasurement(id: string): Promise<void> {

await this.measurementRepository.delete(id)

}

}Yeah! That was a ride! We're done! Go home, Dear Developers. See you in the next sprint! 👋

Changes!

Nothing is certain except for death and taxes... and CHANGES!

In this chapter, I'd like to show you, Dear Reader, how new features can put the codebase to the test and demonstrate how your components will evolve.

You need only one change to turn your assumptions upside down.

Change One

The doctor wants to view priority patients, i.e., those for whom a big alert has been raised.

I asked Claude Code (Sonnet 4.5) to implement the change.

Look at Image 6, where the changes are highlighted. The most obvious place for the new piece of code is the User entity. Image 6 shows the modifications applied to UserRepository. The change is effortless, right? We have joined the Users and Alerts tables by the foreign key (userId) and filtered the patients who have a raised significant alert (and the alert is still active).

What do you think about this?

Risks ⚠️

Let's critically analyze the recent changes:

User/PII (eng. Personally Identifiable Information).

It means that if the team gets two tasks — one is to add an ID number and the other is to extend the definition of the Priority Patient — then the changes will be applied to the same file, to the same entity. If the team works with a relational database and relies on migrations, then the conflict will spread to the migrations as well. Additionally, working on the same components forces more inter-human communication, which is costly. This is the coupling created between two features: PII and Priority Patients.

User entity.

Users with the Alerts table. The Alert entity is used to make business decisions (whether alerts should be raised). This is dangerous, as by implementing a new feature that has nothing to do with alerting, we may impact the alerting logic.

isPriorityPatient flag, so there's no need to perform the join every time.

The coupling problem remains the same, but this solution is even worse because it extends the User entity with a new property.

The team I currently work with inherited a codebase where the Patients table has been weighted down with so many flags and properties that DynamoDB reported that a single row/document is too big and cannot be loaded at once from the drive!

This is the most outstanding and largest example of coupling I have seen in my life.

Change Two

Doctors need to determine the severity of a given alert on a scale of "low", "medium", "high", "critical".

I asked Claude Code (Sonnet 4.5) to implement the change.

What do you think about this?

Risks ⚠️

importance property to the Alert entity. The problem is that the new property is needed for the view, not for deciding about raising or resolving alerts. Thus, we've just mixed up a write model with a read model. As with Change One, this means that when changing things for a view, it may cause a regression in the alerting logic.

Change Three

Doctors want to calculate a new risk level: the risk of fatty liver disease. This generates small alerts without affecting big ones.

The business and its capabilities evolve and change; the business adapts to the market and the competitors. That's why the company's owner, after consultation with stakeholders (medical doctors), decided that the system should be able to determine the risk of a fatty liver. That should eventually bring in more new customers.

I asked Claude Code (Sonnet 4.5) to implement the change.

The test for whether a new alert should be raised when it turns out there is a significant risk of fatty liver was added (according to the architecture and its logic) to the Alert entity.

It's worth noticing how this new method, checkFattyLiverRisk, is being called in the related service. You can see it in Image 10.

Risks ⚠️

Alert entity (within the same context).

This is coupling, but now between two write models. The newly added check requires the patient's sex, ALT, and fibrosis levels to be calculated.

Alert service, we see a pretty lengthy dictionary containing Alert, Measurement, and User.

Think also that the checkMeasurement method is called in the Measurement service. It's all tangled together and connected to each other. We can start thinking of the tangled objects as a big ball of mud.

Alert entity got pretty big. Imagine that further changes will add more tastes and smells to this class, which has started becoming spaghetti code and a God Class.

Other changes

Let's consider the following requirement:

The integrating clinic wants to introduce its own risk calculation formula

Nothing simpler, right? Following the current architecture and the way of work, the team decides, yet another time, to extend the Alert entity and implement the new logic, a new decision model, alongside the previous ones.

Thus, we keep increasing the features coupling within the alerting part.

This process will go deeper because such integrations are popular. A new signed contract is a potential new integration with another clinic or hospital.

Let's take another requirement:

Doctor wants to display liver cancer risk levels

While the team thinks about this feature during another planning session, it concludes that the change needed is not trivial. It turns out that currently the system does not persist calculated risk levels; instead, it analyzes the input data each time. However, the team believes they can just store the risk level in alerts. But someone else from the team, someone more analytical, says that alerts contain only risks that exceeded the threshold. Thus, to implement the feature, the team would have to store those values separately.

But here comes the question. Maybe the team hasn't discovered some entities in the first place?

Prediction of Alert evolution

We know enough to predict how the Alert entity (by that, I understand the domain part, but also the repository, service, and controller — in general, a place containing features grouped under one context) will evolve. And the future is not bright for it.

We've already learned that the Alert includes various features grouped under the Alert flag.

See a line chart in Image 11 demonstrating how the coupling of the contained features in Alert increases over time when new features are implemented.

When coupling rises, cohesion decreases.

When we know more, let's check the diagram again

After seeing how the codebase evolves and knowing the weak spots, we can critically examine the classes diagram again.

Image 12 highlights the doubts that arose.

Users, that is, who exactly?

Priority patients have been implemented in Users, thus Users suffers the same way as Alerts when it comes to increasing coupling. Even more so, because "User" is very broad in its meaning.

Does user mean the same for measurements? Does user mean the same for alerting? Does user mean the same for the function that calculates the fatty liver risk?

Alert entity: user, ALT, fibrosis, measurement. Next, we added also dependency to fatty liver. Alert encapsulates the whole domain. Alert context violates other contexts, their internals leak into Alert.

measurement or alert, is a good one to start with in the modeling process.

Looking at the Alert class, we see many different nouns, which suggests that they should likely belong to separate entities.

user object in Alert.

We needed the birth date (and later the sex as well), but we provided the whole user object — the same one that contains sensitive data and lots of unnecessary things.

It's technically possible and tempting to access other properties besides the birth date and sex. The contract between Alert and User entities is not defined, so Alert can reach any property of User.

Keeping this in mind — should we also know anything about the internal logic of liver risk or fatty liver calculation?

The Bad Parts

I pointed out a lot of issues in the current implementation, and this is the time to group all of them into Bad Part Practices.

We already discussed one Bad Part, Wireframe Driven Development. See other bad practices.

The Bad Part: Noun(ing)

Nouning is a way of working when development teams build domain models around nouns rather than behaviors. The undesirable effect is that models grow too much, having loosely related behaviors. Such models are characterized by low cohesion and high coupling of contained behaviors. Often, such noun-based models are just read models.

In User, we mixed up personal data together with information about whether a patient is a priority.

In Alert, we tied together a few different behaviors:

- read model (type, timestamps, status, important flag)

- write model - calculating risk of liver cancer

- write model - calculating risk of fatty liver

- write model - should a small alert be raised

- write model - should a big alert be raised

We created highly coupled models, and their maintenance will become a bottleneck over time.

Eventually the models will become:

- God objects

- Spaghetti code

Splitting the models into smaller files referenced in the main file won't change the situation a bit.

The Bad Part: No separation of read and write models

No separation of read and write models means that there is one model that contains both a read and a write model. This is bad because changes in views will impact the write models, which represent business logic. Moreover, the write models will have access to data they don't require. This is a contractual issue because it's not explicit what data is actually needed in the write model, so when a property gets renamed or deleted, we can introduce a bug in the write model. This might also be a security vulnerability. Think of it like a violation of the Liskov Substitution Principle at the architecture level.

The perfect example of combined write and read models is Alert.

The Bad Part: No Clear Contexts

No clear contexts means different parts of the domain leak between domain entities, so in the end, everything depends on each other and no business process is protected from a change in other parts of the system. Even a change to a read-only property may cause damage. This is what a true big ball of mud means.

With better modeling hygiene, we should've created a strong separation between domain entities and the contexts that include them. For instance, create a Patient read model for Alert, which would store only the necessary data, such as birth date and sex. Thanks to that, a change in User, the source of PII, wouldn't impact Alert.

The Bad Part: Context violation / Cross-Context Coupling

A context violation happens when logic that belongs to one business domain is executed inside another domain, causing their models and responsibilities to be mixed. On the other hand, cross-context coupling means two domains are tied together so tightly that one cannot change without breaking the other. Context violation is when we tightly couple domain processes and behaviors, so they impact each other.

This is what happens in MeasurementService:

// Trigger alert checking

await this.alertService.checkMeasurement(user, type, value)This is also broken for alerts:

- No separation of users

- Implementing different business processes that depend on the same entity and the same data

Think of calculating liver cancer risk, calculating another risk after integration with a new clinic, and calculating fatty liver risk. They are separate processes but tied together in Alert.

The Bad Part: Dependency Injection over Events

The Dependency Inversion Principle of SOLID defines how to create loosely coupled objects. The most popular method of implementing this principle is dependency injection, but it still creates high coupling. In contrast, another method of implementation is events. Events, in fact, create loosely coupled contexts (not entirely — context violation is still possible).

This is not a bad part on its own, but it can be, like in our case. Imagine how the implementation would look with events and how side effects would be handled when a new measurement gets registered.

The Bad Part: Leaking the Domain

Leaking the domain occurs when internal business rules, calculations, or decision logic escape their intended boundaries and become accessible or dependent on unrelated parts of the system. This often happens unintentionally when entities or services expose too much data or behavior, making it easy for other parts of the codebase to rely on implementation details rather than explicit contracts.

In the example presented, the Alert entity exposes detailed knowledge about patient data, measurements, and medical risk calculations. Over time, other services begin to depend on this leaked knowledge. Once this happens, changing the domain logic becomes risky because external components may rely on assumptions that were never meant to be public.

Leaking the domain makes refactoring dangerous, slows down development, and creates hidden dependencies that are difficult to track and reason about.

The Bad Part: No Ubiquitous Language

No ubiquitous language means the code and business diverge. Developers, domain experts, and stakeholders use different terms, leading to miscommunication, inconsistent implementation of business rules, and fragile or ambiguous systems. The domain model becomes harder to understand, maintain, and evolve, and integration between bounded contexts is error-prone. A shared language is essential to ensure clarity, correctness, and alignment between the software and the business.

In the example, we defined a user. But who is that, in fact? Is the user responsible for what exactly? What does user mean for measurements? What does user mean for alerts?

The Bad Part: No Actual Design Phase

Skipping or minimizing the design phase often feels productive in the short term. After all, writing code gives immediate results, while design discussions can feel abstract or slow.

However, the absence of a real design phase usually means that:

- Requirements are translated directly into code

- Wireframes become architectural drivers

- Domain concepts are discovered after implementation

- Refactoring becomes the primary design tool

In this article's example, the system was designed implicitly through REST endpoints, entities, and database tables. Architecture emerged accidentally rather than intentionally.

Design is not about drawing diagrams — it is about discovering boundaries, responsibilities, and invariants before they become expensive to change.

The Agile methodology is not the answer, because if you split initial design/architecture work into a few sprints, your architecture will become uncontrolled and undirected.

The Bad Part: Instrastructure over domain

Infrastructure over Domain occurs when a development team favors design patterns and off-the-shelf architectures over a deep understanding of the business domain and the discovery process. As a result, the focus shifts to technical concerns rather than accurately mapping business processes into the codebase.

When design patterns and off-the-shelf architectures are applied without sufficient domain knowledge or experience, they can push the codebase toward an infrastructure-first solution or even a “No Actual Design Phase” anti-pattern.

Examples of such patterns and architectures include:

The Bad Part: Data Coupling

Data coupling occurs when contexts cannot be separated because they use shared data (tables, documents, etc.).

Imagine we want to physically separate two business capabilities: registering measurements and alerting. Alerting is critical, and we decided to put it into a separate infrastructure, which means a separate service.

But here comes the real and big issue. What to do with the data?

When deciding whether an alert should be raised, Alert reads the Users table. What to do with Users, then? Should Alert request users or store its own read model?

Database relationships can become heavy chains — the relationships should not cross contexts; If they do, then one context is able to read data of another context, which leads to having a contract by database (shared database) - a well-known anti-pattern descibed in Enterprise Integration Patterns: Designing, Building, and Deploying Messaging Solutions.

Read about how to proceed with database decomposition.

Shared persistence is the strongest form of coupling.

Wrap-up

This article intentionally showcased a system that works but evolves poorly.

None of the problems described appear catastrophic at first. In fact, many of them look reasonable, familiar, and even "best-practice compliant" when viewed in isolation. The real danger lies in how these decisions compound over time.

What we observed was:

- Growing coupling between unrelated features

- Blurred domain boundaries

- Entities overloaded with responsibilities

- Read and write concerns mixed together

- Architecture driven by UI and persistence rather than behavior

If we don't model the domain, we end up with an accidentally evolved codebase — high coupling, low cohesion, and a tangled mess that becomes harder to change with every commit.

This is the old Single Responsibility Principle applied at the architectural level. Consider the Alert entity: liver cancer risk, fatty liver detection, measurements, users — if we modify a module for more than one reason, we've already lost the battle.

Through shallow modelling, we probably haven't discovered all the entities we need. Think about:

- Write models:

Evaluation,RiskAssessment - Read models:

PatientCondition,PriorityPatient - Or even better write models:

calculateLiverFattyRisk,calculateLiverCancerRisk - And read models:

Alert,Evaluation,PriorityPatient, etc.

One of solutions you can find in my previous article: Events are Domain Atoms.

The write model ≠ the read model. When a single table like Alert serves both views and business decisions, adding view-only information (like alert importance) pollutes the write model.

Watch out for domain leaks. If concepts like user or measurement leak into the alert module, it becomes too easy to reach for more related information — and suddenly everything depends on everything.

The term User is too generic — it attracts too many potential features. A priority patient feature shouldn't live in a generic user model. Patient, Doctor, Admin, LabTechnician — these are different concepts. Even Patient means different things in different contexts. The classic example is Product — it's never just one thing across an entire system.

Data coupling through database relations creates strong dependencies that are always technically difficult to untangle. When making a business decision about raising an alert, you shouldn't need to reach into the Users table. Relationships in the database create tight coupling, and disentangling them is always technically painful.

Bad architecture is rarely the result of incompetence — it is usually the result of good intentions applied without sufficient domain insight.

Separation techniques applied to discovered contexts, such as data redundancy, have a higher entry threshold, but the payoff comes later. If your project follows a waterfall model and the full scope is known upfront, then the solution presented in this article may be sufficient. However, if the project has the potential to grow, I see no reason to skip the architecture and design phase.

Everything is a tool. If you don’t know how to build event-driven architectures, haven’t applied CQRS, or aren’t familiar with event sourcing or DDD, these are simply skills to learn and adopt—just like any other tool in your current toolset.

•••

See you later.

Artur.

HermesJS 🫒🌿

But you miss a lot of things in this ecosystem. You miss a chassis.

Hermes PostgreSQL and Hermes MongoDB are part of the initiative that delivers to you a foundation of a reliable system.

It is a library, not a framework, which relies on PostgreSQL's Logical Replication / MongoDB Change Stream.

It implements the Outbox pattern. You can span a database transaction over persisting an entity and publishing a message.

Go to the docs!

Give a start on the GitHub!